This small house is located on 8x20m lot in Pondok Indah district. Although it is a part of gated community, this building located on the edge small river with a village right across the river. Pondok Indah in South Jakarta is a residential area which is indeed successfully built in the 80’s. since then, Pondok Indah is being a symbolic status. Some of the most successful parliament member in Jakarta as well as some celebrities who come from other regions feel like a must-have house in this area. This symbol of success is generally showed by architectural language. For instance, structural column is similar to that of Italyor France. This pillar shows a success. To answer this challenge, the designer starts to ask the homeowner whether she still needs those symbol or vice versa. It turns out that she agrees to demolish this situation by deconstructing this common discourse, tilting the whole house to be something that almost fals down. This house is also next door of Indonesian musician, Ahmad Dhani. His house is painted totally black whereas this house is all white. This unintentionally coincidence reinforces (Slanted House) as an architecture which criticizes it environment. The spatial function of the house uses a new sequence. The public area is placed on the first floor, which consists of pantry, study area and swimming pool. Second level has private rooms such as master bedroom, wardrobe and bathroom. The bathroom acts as a response to the current trend of urban lifestyle. People normally spend more time in a bathroom for quiet time and contemplative room while using smart phones, reading newspaper or social media as a communication device. The top level is used for lounge and guest room. In the building section, the private area is put in the middle, like a sandwich between public areas. The whole building relies on the steel structure as a representative of a modern housing which depends on fabrication. This framework is now agreed to be slanted as a symbol of instability and a deconstruction of surroroundings.

Visionary Future LAB is a weblog devoted to the future of design, tracking the innovations in technology, practices and materials that are pushing architecture, interior, product design and urbanism towards a smarter and more sustainable future. Visionary Future LAB was started by Jakarta based research architect Budi Pradono as a forum in which to investigate emerging design in product, interior and architecture & urbanism

Monday, September 19, 2016

Sunday, September 18, 2016

Publication : Asean Architect 04 - Budi Pradono Architects Indonesia in ASA Magazine - Architect'16 Review, Thailand no 03 / 2016

This fourth installment in the series of articles on

selected young ASEAN practices is focused on an Indonesian design studio that

has gained much traction in the industry in this region with their distinctively

exploratory approach to architectural design. Budi Pradono Architects (BPA),

founded in 1999, is a research based architectural studio with an

interdisciplinary focus on inclusive rigorous methodologies of research,

collaboration and experimentation. It believes in the concentration om the

characteristics and specificities of each and every project as part of its

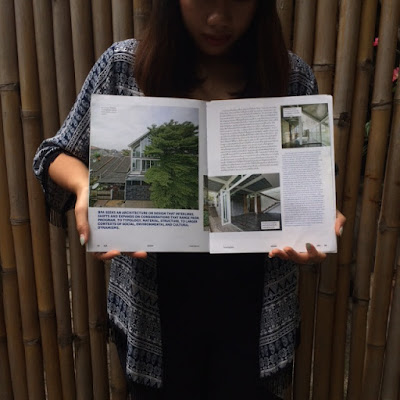

individuality and conditions that surround it. BPA seeks an architecture or

design that interlinks, shifts and expands on considerations that range from

program, to typology, material, structure, to larger contexts of social,

environmental and cultural dynamisms. It engages itself on various scales of

project to relate design in search of connectivity and relation at multiple

levels and facest – be it product design, or urban infrastructure. BPA pursues

a resonance in the creative explorations during the design process as an

opportunity for connections and relations. A selection in three of the studio’s

project is presented here to explore this perspective.

The first example to illustrate BPA’s design

philosophy of connecting architecture with its users and environment is the A

House. The 183-sqm residence, located at a corner af a street in Bintaro area

in the periphery of Southern Jakarta, was designed around an existing 9m-tall

Ketapang Kencana tree. The design team first sought to preserve the tree and

used it as a guiding principle design element by organizing living spaces

around and in relation to the tree. With an objective to achieve a ‘home with

environment as a new oasis to live’

several fundamental questions were raised during the design process – such as

‘what if the bed is on top of the tree?’, ‘what if the homeowner can do the

contemplation in the bathroom, in the middle of the tree?’ etc. Some additional

trees were also planted on site to amplify this feeling of living in a jungle.

To translate the idea into reality, the design team inserted the master bedroom

with its en-suite bathroom on the 3rd floor – 8m above ground, among the tree

canopies. Some parts of the roof is made with a glass skylight to bring in

natural light and to induce a stack effects of air movement from the bottom of

the house up to the roof level. A ceiling with reflective material was

additionally applified throughout the house to give it a character and to

reflect the light from the outside and the tree silhouettes. The living room is

placed on the 2nd floor adjacent to the lower part of the tress, with an

intended increased visibility to the branches, where by the noisier 1st floor

houses the pantry and dinning room. To mitigate noise pollution stemming from

motorcycles passing by every morning and evening, a barrier wall with its

stepped down section toward the inside of the house is provided. The amphittheatre-like

shape of the wall is used as additional seating area for the dinning room. It

is intended that this micro-scaled home greening strategy would eventually

contribute to a greener Bintaro district.

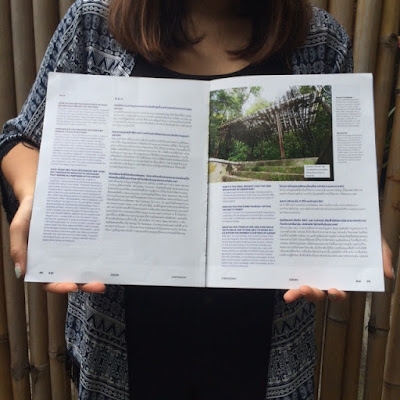

This relationship between architecture and its

surroundings was further explored in the Dancing Mountain House project. Here,

instead of designing a house around a tree, the approach was tested on a much

larger scale – to mimic the topographic character of its natural setting at

2.000m above the sea level on the ridge of Mount Merbabu, and with it being

surrounded by several other mountanis. The project was conceptualized by

interpretation of the multiplication of Javanese village houses and the

reinterpretation of the traditional roof structure by adding the

mountain-shaped roof features which serve as skylight to bring as much natural

light as possible into the building.

The structure was made entirely out of bamboo with

traditional techniques assisted by new construction technology. Local materials

such as brick, bamboo and stone were used in differing ways. There was, in

addition, a starategy to utilize recycled and reused from the old house that

used to be sited there. What is more surprising is the fact that the house was

not built by a professional contractor but by the local community at large. The homeowners are both retired

lecturers who wanted to share their collection of economic and science books to

the surrounding community, so there is a part of the house that is dedicated to

serve as a library that can be accessed freely by the local people. To

summarize, this house is a noteworthy example of how architecture can engage

various aspect of social and economic drivers and putting them together to

function.

A concept similar to the Dancing Mountain House is

applied once more for the design of I-Shelter, a 30-sqm bike race shelter for

the Tour de Ijen, an event organized annually in Banyuwangi of East Java. The

form of the shelter was derived by mapping the height of mountains and the

depth of volcanic craters in the region, a method referred to by BPA as the

‘Specificity Of Place’. The fragment formation of such topography is then

realized three-dimensionally by the stacking of 5mm wide bamboo laths

vertically and horizontally. The whole shelter is made of Petung bamboo that

can be found around Gunung Ijen, a building material that was preserved

traditionallly by soaking it in the river for 8 months before use. A layer of

polycarbonate sheet is then slipped into the centre of the bamboo roofrops to

make the shelter functional. This location is also well known as a popular

hiking trail, where the shelter can be used as a resting spot for hikers and

bikers outside of the competition tournament. Though small in size, BPA

believes im how architectural design can become a device for making more

meaningful places rather than just functioning as nere shelters. As aptly

stated by Budi Pradono, ‘I believe that a small project is a chance as well as

a challenge for an architect to build a strong concept and also to utilize

architecture as a device to elevate local strengths, re-elevate the local

preservation method which has long been forgotten, as well as creating a unique

and specific place’.

BPA’s works ilustrate that there are several ways in

which the surround and context-natural of human, can be integrated in the

initial approaches to architectural design. A sensitivity and respect to the

givens in context can work together with building techniques to conjure

meaningful spaces, and subsequently social communities. These are frameworks

upon which BPA challenges themselves to rethink, reevaluate and inform in the

basic necessities of buildings and surroundings in their work. The attention to

social and environmental awaremesses and the responsibilities that carry along

with them, adds yet another dimension to the mere intrinsic nature of buildings

and shelters. When carried across a multitude of scales and sites, the results

can often produce appropriate and enlightening responses that delights an

enriches, hences providing that connectivity that is often so critical in

engaging both project requirements and site locale together. This thus becomes

a paramount attribute that illustrate and perhaps should inspire architectural

practices on how they can engrain themselves in the context that they operate –

responsibly.

Q & A

HOW DO YOU SEE THE IMPORTANCE OF

IDEAS BEHIND EACH PROJECT OF THE FIRM?

Each place or project has a hidden and specific

characteristic. This is where we are very interested at exloring more in local

environment characteristic, such as wind, lighting, as well as local material,

or space program required by clients. The invisible character that we found in

the field may be become our tools so that it can create such new ingredients

for a new architecture.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE THE FIRM’S

APPROACH TO ARCHITECTURE?

BPA as a research based architecture firm uses a

variety of methods in each project for finding the invisible characteristics of

a site; that even is able to gather standard programs to be the new ones. Thus,

we are very glad to have collaborated with a variety of disciplines, so that we

can obtain new things in the design process. Another strategy is using mock-up

models and 3D software as both tools in parallel procedures. In this process,

it creates space and the experiment of programming and materials in which, I

believe by making the real model in scale is very important, it can allow the

space to be intuitionally felt directly. This stage is very crucial to us.

WHO/WHAT ARE YOUR INFLUENCES? ARE

THERE ANY PARTICULAR ARCHITECTS/DESIGNER THAT INSPIRE ALL PARTNERS IN THE

OFFICE?

During my study in my undergraduate program in

Yogyakarta, I have explored the architecture approaches by Bernard Tschumi who

wrote “Manhattan Transcript”, a book mainly focusing on the dis-programming

theory. At the same time I was also interested at studying any theories on

deconstruction architecture, maninly expressed by Peter Eisenman giving

questions on status quo of modern architecture. After I had graduated, I was in

obsession with Rem Koolhaas’ writings in S M L XL, as well as I started to love

and like the architectural works by Tadao Ando, a Japanese architect, whose

works I visited throughout the world. However, the one that gave me the

architecture view and strength before I opened my own practice was Kengo Kuma.

I worked with him for two years in Tokyo, and had the opportunity to explore

architectural design in millimetre scale sizes. As I further studied in broader

scale (urban scale) from Winy Maas (MVRDV) under his studio at the Berlage

Institute in Rotterdam Netherlands, I came across studies in kilometre scales,

it required me to lay the grounwork for design methods that propose

contemporary architecture.

WHAT IS THE IDEAL PROJECT THAT THE

FIRM WOULD LIKE TO UNDERTAKE?

The ideal project is both small project an big

project. In millimetres and kilometres, both have very extreme difference. We

expect that each year we will get two types of these projects.

HOW DO YOU POSITIONS YOURSELF WITHIN

THE NEXT 5 YEARS?

In the next five years, the researches by BPA

hopefully can collaborate with the programs in some of the universities in the

world, so that these will create further innovations in architectural design.

WHAT DO YOU THINK OF AEC AND HOW ARCHITECTS

ARE IN THE FUTURE ABLE TO WORK EASILY WITHIN THE MEMBER COUNTRIES OF ASEAN?

With AEC, we should study with those in Europe. There

must be integration between ASEAN level competitions concerning the public

building such as campus, schools, as well as social housing. The similarity of

climate and material can be anticipated simultaneously, meanwhile these will

give new strength for ASEAN to get rapid new generation with specific

characters. As for the cooperation with universities, it must also be encouraged,

so that there will not only be a platform of cross culture but also a platform

for cross knowledge, which is neccessary for the future of ASEAN architecture.

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

Saturday, February 20, 2016

Friday, February 19, 2016

Dancing Mountain House on d+a singapore

NATURE IN DESIGN

d+a design and architecture

DANCING MOUNTAIN HOUSE

Budi

Pradono builds a family home made of bamboo for a retired couple that mimics

the peaks of nearby mountains in central Java

text

Rebecca Lo // PhotograPhy FeRnando GomuLya and FX bambanG Sn

where they can view the waltzing mountains within a generous

space they occasionally share with children and grandchildren returning from

abroad.

‘Along with being a university educator, my client was a father

figure and democratic freedom fighter during (the late Indonesian) President

Suharto’s regime,’ says Pradono. ‘The couple has a collection of science and

economic books that they wanted to share with the surrounding community in a

sort of public library. They appreciated the bamboo structures which the

community is beginning to abandon, and they wanted to learn more about this

renewable material. I ended up seeking an expert in bamboo construction, as

bamboo forms the main structure. I also found a village full of bamboo

furniture craftsmen not far from the site.

‘The home is in a rural area and is surrounded by trees. Its

shape is rather triangular, with a steeper side so the land appears wider than

it actually is. The most difficult task was bringing memory into the new house.

Since the owners’ children live in Berlin and Sydney as well as Timor-Leste,

Yogyakarta and Jakarta, the house has to have the spirit of home. This spirit

was translated into a large open space, using waste materials salvaged from

their old house, such as timber window frames or teak doors.

‘In plan, the dining room became the home’s centre. For 30

years, this family relied on the dining table as the centre for all activities,

as well as a knowledge generator and communication device. It was a tool to

communicate creative ideas, talk about international politics or trivial

matters surrounding the funny events in the village; a place to share stories,

eat together, a place to learn and meet. Other programmes in the house

were arranged linearly from the dining room. The main bathroom

near the home’s entry is a semi- enclosed, social space that allows for

dialogue as the walls are just under 2.2 metres. It reflects our childhood in

the 70s when the activity of doing laundry or bathing in the river was also a

time to share many things. The side of the building towards the park was left

open to represent the house’s concept of being borderless – a nod to my

client’s political past.’

The house is laid out along the south end of the site, with

public areas such as the large kitchen and dining area taking up the front

portion. This is a reversal of the hierarchy found in traditional Javanese

homes, where the pendana or front of

the house is where men welcomed guests and the pawon or

back of the house is where women are relegated to do the cooking. Pradono’s

concept echoes the peaks of the nearby mountains with bamboo roof structures

that form cones above each area. The house’s structure relies on locally

available materials, such as petung bamboo with diameters of 12 to 15

cms used as angled support columns. Walls are clad with glass and steel, with

red brick delineating perimeters; floors are exposed concrete, chapped bamboo

in bedrooms and andesit stone in bathrooms. Natural sunlight is encouraged

through full-height glazing to reduce the reliance on artificial lighting,

while water is heated using solar panels for hot morning showers in the chilly

mountainous climate.

‘The house activated the surrounding communities,’ says

Pradono. ‘At the beginning of the project, I mapped the region and found many

interesting materials such as bamboo, bricks, clay and stone, which were all

available very close to the site. Approximately 20km away, in a village called

Sekarlangit, there are many cottage industries that manufacture bamboo battens

and rafters. We made the house’s rafters from petung bamboo, split into

five centimeter widths and then soaked into the river for three to six months;

this reduces their glucose and makes them ready for building. The owner became

his own project manager, to save on costs. We also engaged the local craftsmen

and the surrounding community to build together. There is an oval shaped space

to one side of the house designed as a study and small library. It is open to

the local community to come, read the books and learn with their children.’

‘The house activated the surrounding communities,’ says

Pradono. ‘At the beginning of the project, I mapped the region and found many

interesting materials such as bamboo, bricks, clay and stone, which were all

available very close to the site. Approximately 20km away, in a village called

Sekarlangit, there are many cottage industries that manufacture bamboo battens

and rafters. We made the house’s rafters from petung bamboo, split into

five centimeter widths and then soaked into the river for three to six months;

this reduces their glucose and makes them ready for building. The owner became

his own project manager, to save on costs. We also engaged the local craftsmen

and the surrounding community to build together. There is an oval shaped space

to one side of the house designed as a study and small library. It is open to

the local community to come, read the books and learn with their children.’

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)